In 2005, after just two weeks, Linus Torvalds completed the first version of Git, an open-source version control system. Unlike typical centralized systems, Git is based on a distributed model. It is extremely flexible and guarantees data integrity while being powerful, fast and efficient. With widespread and growing rates of adoption, and the increasing popularity of services like GitHub, many consider Git to be the best version control tool ever created.

Surprisingly, Linus had little interest in writing a version control tool before this endeavor. He created Git out of necessity and frustration. The Linux Kernel Project needed an open-source tool to manage its massively distributed development effectively, and no existing tools were up to the task.

Many aspects of Git's design are radical departures from the approach of tools like CVS and Subversion, and they even differ significantly from more modern tools like Mercurial. This is one of the reasons Git is intimidating to many prospective users. But, if you throw away your assumptions of how version control should work, you'll find that Git is actually simpler than most systems, but capable of more.

In this article, I cover some of the fundamentals of how Git works and stores data before moving on to discuss basic usage and work flow. I found that knowing what is going on behind the scenes makes it much easier to understand Git's many features and capabilities. Certain parts of Git that I previously had found complicated suddenly were easy and straightforward after spending a little time learning how it worked.

I find Git's design to be fascinating in and of itself. I peered behind the curtain, expecting to find a massively complex machine, and instead saw only a little hamster running in a wheel. Then I realized a complicated design not only wasn't needed, but also wouldn't add any value.

Git, at its core, is a simple indexed name/value database. It stores pieces of data (values) in “objects” with unique names. But, it does this somewhat differently from most systems. Git operates on the principle of “content-addressed storage”, which means the names are derived from the values. An object's name is chosen automatically by its content's SHA1 checksum—a 40-character string like this:

1da177e4c3f41524e886b7f1b8a0c1fc7321cac2

SHA1 is cryptographically strong, which guarantees a different checksum for different data (the actual risk of two different pieces of data sharing the same SHA1 checksum is infinitesimally small). The same chunk of data always will have the same SHA1 checksum, which always will identify only that chunk of data. Because object names are SHA1 checksums, they identify the object's content while being truly globally unique—not just to one repository, but to all repositories everywhere, forever.

To put this into perspective, the example SHA1 listed above happens to be the ID of the first commit of the Linux kernel into a Git repository by Linus Torvalds in 2005 (2.6.12-rc2). This is a lot more useful than some arbitrary revision number with no real meaning. Nothing except that commit ever will have the same ID, and you can use those 40 characters to verify the data in every file throughout that version of Linux. Pretty cool, huh?

Git stores all the data for a repository in four types of objects: blobs, trees, commits and tags. They are all just objects with an SHA1 name and some content. The only difference between them is the type of information they contain.

A blob stores the raw data content of a file. This is the simplest of the four object types.

A tree stores the contents of a directory. This is a flat list of file/directory names, each with a corresponding SHA1 representing its content. These SHA1s are the names of other objects in the repository. This referencing technique is used throughout Git to link all kinds of information together. For file entries, the referenced object is a blob. For directory entries, the referenced object is a tree that can contain more directory entries, in turn referencing more trees to define a complete and potentially unlimited hierarchy.

It's important to recognize that blobs and trees are not themselves files and directories; they are just the contents of files and directories. They don't know about anything outside their own content, including the existence of any references in other objects that point to them. References are one-way only.

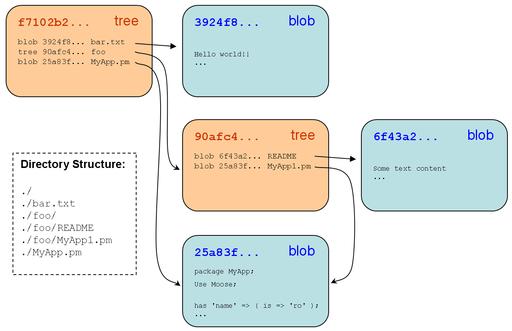

Figure 1. An example directory structure and how it might be stored in Git as tree and blob objects (I truncated the SHA1 names to six characters for readability).

In the example shown in Figure 1, I'm assuming that the files MyApp.pm and MyApp1.pm have the same contents, and so by definition, they must reference the same blob object. This behavior is implicit in Git because of its content-addressable design and works equally well for directories with the same content.

As you can see, directory structures are defined by chains of references stored in trees. A tree is able to represent all of the data in the files and directories under it even though it contains only one level of names and references. Because SHA1s of the referenced objects are within its content, a tree's SHA1 exactly identifies and verifies the data throughout the structure; a checksum resulting from a series of checksums verifies all the underlying data regardless of the number of levels.

Consider storing a change to the file README illustrated in Figure 1. When committed, this would create a new blob (with a new SHA1), which would require a new tree to represent “foo” (with a new SHA1), which would require a new tree for the top directory (with a new SHA1).

While creating three new objects to store one change might seem inefficient, keep in mind that aside from the critical path of tree objects from changed file to root, every other object in the hierarchy remains identical. If you have a gigantic hierarchy of 10,000 files and you change the text of one file ten directories deep, 11 new objects allow you to describe both the old and the new state of the tree.

A commit is meant to record a set of changes introduced to a project. What it really does is associate a tree object—representing a complete snapshot of a directory structure at a moment in time—with contextual information about it, such as who made the change and when, a description, and its parent commit(s).

A commit doesn't actually store a list of changes (a “diff”) directly, but it doesn't need to. What changed can be calculated on-demand by comparing the current commit's tree to that of its parent. Comparing two trees is a lightweight operation, so there is no need to store this information. Because there actually is nothing special about the parent commit other than chronology, one commit can be compared to any other just as easily regardless of how many commits are in between.

All commits should have a parent except the first one. Commits usually have a single parent, but they will have more if they are the result of a merge (I explain branching and merging later in this article). A commit from a merge still is just a snapshot in time like any other, but its history has more than one lineage.

By following the chain of parent references backward from the current commit, the entire history of a project can be reconstructed and browsed all the way back to the first commit.

A commit is expanded recursively into a project history in exactly the same manner as a tree is expanded into a directory structure. More important, just as the SHA1 of a tree is a fingerprint of all the data in all the trees and blobs below it, the SHA1 of a commit is a fingerprint of all the data in its tree, as well as all of the data in all the commits that preceded it.

This happens automatically because references are part of an object's overall content. The SHA1 of each object is computed, in part, from the SHA1s of any objects it references, which in turn were computed from the SHA1s they referenced and so on.

A tag is just a named reference to an object—usually a commit. Tags typically are used to associate a particular version number with a commit. The 40-character SHA1 names are many things, but human-friendly isn't one of them. Tags solve this problem by letting you give an object an additional name.

There are two types of tags: object tags and lightweight tags. Lightweight tags are not objects in the repository, but instead are simple refs like branches, except that they don't change. (I explain branches in more detail in the Branching and Merging section below.)

If you don't already have Git on your system, install it with your package manager. Because Git is primarily a simple command-line tool, installing it is quick and easy under any modern distro.

You'll want to set the name and e-mail address that will be recorded in new commits:

git config --global user.name "John Doe" git config --global user.email john@example.com

This just sets these parameters in the config file ~/.gitconfig. The config has a simple syntax and could be edited by hand just as easily.

Git's interface consists of the “working copy” (the files you directly interact with when working on the project), a local repository stored in a hidden .git subdirectory at the root of the working copy, and commands to move data back and forth between them, or between remote repositories.

The advantages of this design are many, but right away you'll notice that there aren't pesky version control files scattered throughout the working copy, and that you can work off-line without any loss of features. In fact, Git doesn't have any concept of a central authority, so you always are “working off-line” unless you specifically ask Git to exchange commits with your peers.

The repository is made up of files that are manipulated by invoking the git command from within the working copy. There is no special server process or extra overhead, and you can have as many repositories on your system as you like.

You can turn any directory into a working copy/repository just by running this command from within it:

git init

Next, add all the files within the working copy to be tracked and commit them:

git add . git commit -m "My first commit"

You can commit additional changes as frequently or infrequently as you like by calling git add followed by git commit after each modification you want to record.

If you're new to Git, you may be wondering why you need to call git add each time. It has to do with the process of “staging” a set of changes before committing them, and it's one of the most common sources of confusion. When you call git add on one or more files, they are added to the Index. The files in the Index—not the working copy—are what get committed when you call git commit.

Think of the Index as what will become the next commit. It simply provides an extra layer of granularity and control in the commit process. It allows you to commit some of the differences in your working copy, but not others, which is useful in many situations.

You don't have to take advantage of the Index if you don't want to, and you're not doing anything “wrong” if you don't. If you want to pretend it doesn't exist, just remember to call git add . from the root of the working copy (which will update the Index to match) each time and immediately before git commit. You also can use the -a option with git commit to add changes automatically; however, it will not add new files, only changes to existing files. Running git add . always will add everything.

The exact work flow and specific style of commands largely are left up to you as long as you follow the basic rules.

The git status command shows you all the differences between your working copy and the Index, and the Index and the most recent commit (the current HEAD):

git status

This lets you see pending changes easily at any given time, and it even reminds you of relevant commands like git add to stage pending changes into the Index, or git reset HEAD <file> to remove (unstage) changes that were added previously.

The work you do in Git is specific to the current branch. A branch is simply a moving reference to a commit (SHA1 object name). Every time you create a new commit, the reference is updated to point to it—this is how Git knows where to find the most recent commit, which is also known as the tip, or head, of the branch.

By default, there is only one branch (“master”), but you can have as many as you want. You create branches with git branch and switch between them with git checkout. This may seem odd at first, but the reason it's called “checkout” is that you are “checking out” the head of that branch into your working copy. This alters the files in your working copy to match the commit at the head of the branch.

Branches are super-fast and easy, and they're a great way to try out new ideas, even for trivial things. If you are used to other systems like CVS/SVN, you might have negative thoughts associated with branches—forget all that. Branching and merging are free in Git and can be used without a second thought.

Run the following commands to create and switch to a new local branch named “myidea”:

git branch myidea git checkout myidea

All commits now will be tracked in the new branch until you switch to another. You can work on more than one branch at a time by switching back and forth between them with git checkout.

Branches are really useful only because they can be merged back together later. If you decide that you like the changes in myidea, you can merge them back into master:

git checkout master git merge myidea

Unless there are conflicts, this operation will merge all the changes from myidea into your working copy and automatically commit the result to master in one fell swoop. The new commit will have the previous commits from both myidea and master listed as parents.

However, if there are conflicts—places where the same part of a file was changed differently in each branch—Git will warn you and update the affected files with “conflict markers” and not commit the merge automatically. When this happens, it's up to you to edit the files by hand, make decisions between the versions from each branch, and then remove the conflict markers. To complete the merge, use git add on each formerly conflicted file, and then git commit.

After you merge from a branch, you don't need it anymore and can delete it:

git branch -d myidea

If you decide you want to throw myidea away without merging it, use an uppercase -D instead of a lowercase -d as listed above. As a safety feature, the lowercase switch won't let you delete a branch that hasn't been merged.

To list all local branches, simply run:

git branch

Git provides a number of tools to examine the history and differences between commits and branches. Use git log to view commit histories and git diff to view the differences between specific commits.

These are text-based tools, but graphical tools also are available, such as the gitk repository browser, which essentially is a GUI version of git log --graph to visualize branch history. See Figure 2 for a screenshot.

Git can merge from a branch in a remote repository simply by transferring needed objects and then running a local merge. Thanks to the content-addressed storage design, Git knows which objects to transfer based on which object names in the new commit are missing from the local repository.

The git pull command performs both the transfer step (the “fetch”) and the merge step together. It accepts the URL of the remote repository (the “Git URL”) and a branch name (or a full “refspec”) as arguments. The Git URL can be a local filesystem path, or an SSH, HTTP, rsync or Git-specific URL. For instance, this would perform a pull using SSH:

git pull user@host:/some/repo/path master

Git provides some useful mechanisms for setting up relationships with remote repositories and their branches so you don't have to type them out each time. A saved URL of a remote repository is called a “remote”, which can be configured along with “tracking branches” to map the remote branches into the local repository.

A remote named “origin” is configured automatically when a repository is created using git clone. Consider a clone of Linus Torvald's Kernel Tree mirrored on GitHub:

git clone https://github.com/mirrors/linux-2.6.git

If you look inside the new repository's config file (.git/config), you'll see these lines set up:

[remote "origin"] fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/* url = https://github.com/mirrors/linux-2.6.git [branch "master"] remote = origin merge = refs/heads/master

The fetch line above defines the remote tracking branches. This “refspec” specifies that all branches in the remote repository under “refs/heads” (the default path for branches) should be transferred to the local repository under “refs/remotes/origin”. For example, the remote branch named “master” will become a tracking branch named “origin/master” in the local repository.

The lines under the branch section provide defaults—specific to the master branch in this example—so that git pull can be called with no arguments to fetch and merge from the remote master branch into the local master branch.

The git pull command is actually a combination of the git fetch and git merge commands. If you do a git fetch instead, the tracking branches will be updated and you can compare them to see what changed. Then you can merge as a separate step:

git merge origin/master

Git also provides the git push command for uploading to a remote repository. The push operation is essentially the inverse of the pull operation, but since it won't do a remote “checkout” operation, it is usually used with “bare” repositories. A bare repository is just the git database without a working copy. It is most useful for servers where there is no reason to have editable files checked out.

For safety, git push will allow only a “fast-forward” merge where the local commits derive from the remote head. If the local head and remote head have both changed, you must perform a full merge (which will create a new commit deriving from both heads). Full merges must be done locally, so all this really means is you must call git pull before git push if someone else committed something first.

This article is meant only to provide an introduction to some of Git's most basic features and usage. Git is incredibly powerful and has a lot more capabilities beyond what I had space to cover here. But, once you realize all the features are based on the same core concepts, it becomes straightforward to learn the rest.

Check out the Resources section for some sites where you can learn more. Also, don't forget to read the git man page.