Our intrepid writer installs and tests Ubuntu Linux within both VMware Fusion and Parallels Desktop on Mac OS X. Can you really run both Linux and Mac OS X simultaneously and achieve nirvana?

Let's start right off by tackling the most pertinent question for this article: why the heck would someone want to run Linux on a Mac system that already has a very nice Linux distro hidden beneath Mac OS X? Built atop NetBSD, there's quite a bit of Linux sitting there waiting to be utilized in the system, including niceties like crontab, robust account management and much more.

Go to Applications→Utilities, and you'll even find X11, a tightly integrated version of the popular Linux windowing system that plays nicely with the graphical interface that defines the so-called Mac experience. What more could a geek want?

The best answer is simply to quote Sir Edmund Hillary, or perhaps misquote him slightly. Why run Linux on a Mac? “Because you can.” If it just feels too wacked to you, take a deep breath and proceed to the next article in the magazine—no harm done.

Still with me? Great. So let's look at the two ways you can run Linux. You can set up a Mac to dual boot, using Apple's Boot Camp system, which is included with Leopard 10.5 and available for download if you're still running Panther (10.4) from Apple's Web site, but somehow that seems clunky at best given the great virtualization capabilities on modern Apple hardware. As a result, I'm going to focus on getting Linux up and running simultaneously with running Mac OS X.

Two robust applications let you run another operating system within a virtual environment on your Mac: Parallels Desktop and VMware Fusion. The former is a Mac-only company, but the latter might well be familiar to those of you who have run Windows within Linux or Linux within Windows, and so on. I've personally used both products for many years.

I settled on Ubuntu, a Linux distro that has been gaining market share during the past few years and is one of the most popular available. It's also preconfigured for both Parallels and VMware Fusion, so that makes it even better. Free operating systems (that is, anything but Microsoft Windows) can be downloaded easily from vendor sites as a preconfigured data image, alleviating the need to install anything at all—simply download.

Both companies refer to these operating system data images as virtual appliances, and I do so throughout the rest of this article too. You can find Parallels' virtual appliances at ptn.parallels.com, and VMware Fusion's virtual appliances are at www.vmware.com/appliances.

Each repository is impressively broad. For example, the VMware Fusion catalog offers you the ability to download Ubuntu 8.04 alpha 1 or 2, Gentoo 2007.0, PCLinux S, GEubuntu 7.10, OpenSUSE Alpha0, Ubuntu 7.10 Jeos with VMware tools already installed, Linux Mint 4.0 Daryna, and many more Linux distributions, all configured and ready to go. Perhaps even more interesting, you also can download gOS 1.0.1-bagvapp, described as “Google-Wal-Mart's Ubuntu Gutsy-based OS for 'Green PC'”. What Wal-Mart's doing with its own Linux distro, I will leave for another article.

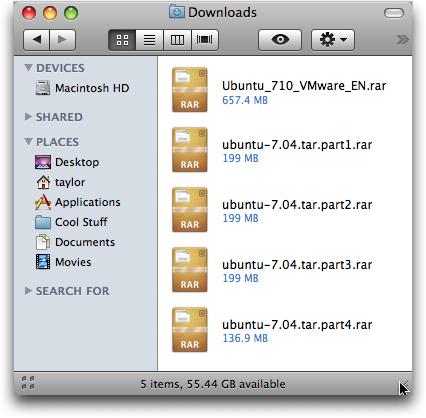

I downloaded Ubuntu 7.10 (Gutsy Gibbon) Desktop—English for VMware Fusion (657MB). Interesting to note, the description states, “perfect to test drive Ubuntu or as a secondary operating system running within Windows.” Windows? We'll see how portable these operating system virtual appliances are I guess. At least it includes a useful set of apps: OpenOffice.org 2.3, Firefox 2, Evolution 2.12, GIMP 2.4, GCC 4.2.1, GNOME 2.20 and X.Org 7.2, all atop Linux kernel 2.6.2.

Downloading files of this size takes us into the world of file sharing: you either can download a single monolithic file in RAR format (RAR stands for Roshal Archive, named after inventor Eugene Roshal) or grab the same file through BitTorrent, which requires a BitTorrent client. I strongly recommend the latter, and I recommend Transmission as the client to use (transmission.m0k.org). It took me a little less than two hours to download this file.

While the Fusion Virtual Appliance was slowly chugging down the pipe and I was waiting for the black helicopters of the MPAA or RIAA to show up and kick in my door (just kidding, mostly, on that last one), I popped over to the Parallels virtual appliance directory. Although better organized, it had considerably fewer appliances available, and there was, in fact, only one reference Ubuntu option, described simply as Ubuntu Desktop. Digging a bit further revealed that it was version 7.04 and was helpfully described as “The virtual appliance is the default Ubuntu Desktop Linux installation. There are various GNOME-based applications.”

That's what I wanted, nonetheless, and at 727MB it was broken into either four 199MB RAR files (yeah, that doesn't add up to 800MB, but you know what I mean) served up by hyperfileshare.com or eight files of 100MB from rapidshare.com. I have to say that this is a significant mistake on the part of Parallels, as these file repositories are confusing, and not having the file accessible through the BitTorrent network is a massive drag. The download is more of a hassle, although it downloaded faster: less than an hour when I, uh, borrowed the network connection at the local café. The biggest problem is that downloads cannot be resumed, while BitTorrent is designed to handle frequent outages, which effectively means you never need to download the same byte twice.

An important thing to note when you do download these virtual appliances is the default user account and password for the OS. For the Parallels virtual appliance, it's ubuntu and the password is 123, and for the VMware Fusion virtual appliance, it's jars, with the password jars. Forget those and you'll be digging through your Web browser history to find the pesky information.

While everything was downloading, I made sure I had downloaded and installed both apps properly, VMware Fusion 1.1 and Parallels Desktop 3.0 Build 5582.0. Both offer fully functional 30-day demo licenses, so you can try Ubuntu in both environments without paying a dime. I used fully licensed commercial versions of the two programs, but they're functionally identical.

Once the virtual appliance files were downloaded, as shown in Figure 1, it was time to unpack them and double-click to see what would happen. Remember, Macs are the computers for the rest of us, so it really should be this easy if the vendors have done their work correctly.

Figure 1. Both the VMware Fusion and Parallels Desktop virtual appliances download as RAR archives, easily handled with Mac OS X.

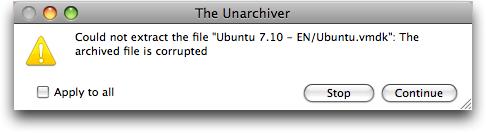

To unpack the RAR archives, I installed and used an application called The Unarchiver, which you can grab from www.versiontracker.com, among other places. I encountered a glitch while unpacking VMware, as shown in Figure 2. I optimistically clicked on Continue, but it didn't work. None of the files extracted were larger than a few dozen KB. Plan B was to download a different Ubuntu virtual appliance, Ubuntu Gutsy Gibbon 7.10 Desktop. And this time, it didn't use BitTorrent, so I watched it slowly download a 468MB image, just to find an archive file ending with .7z, which I'd never seen before. The Unarchiver claimed to deal with 7z archives, but rejected this as corrupted too. Before I gave up though, I downloaded yet another app, 7zX, and after almost 20 minutes, it unpacked successfully.

Figure 2. The first Ubuntu virtual appliance download for Fusion was corrupted, which is darn frustrating after waiting for a 657MB download to complete.

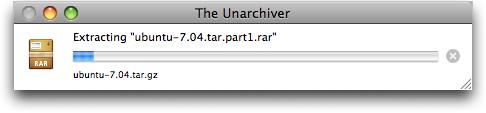

Although the Parallels download comes in four parts, with cheery names like ubuntu-7.04.tar.part1.rar, RAR-friendly apps like Unarchiver automatically concatenate the files. The end result is ubuntu-7.04.tar.gz, which can again be double-clicked on and unpacked to ubuntu-7.04.tar, which again unpacks (why am I reminded of Russian nesting doll puzzles), finally, into the files we seek. The end result is a folder called ubuntu that contains all the necessary files. You can see the files unpacking properly in Figure 3.

Figure 3. It's always exciting to watch a progress bar. This one shows Parallels Desktop virtual appliance Ubuntu 7.04 unpacking from the RAR archive into a .tar.gz file.

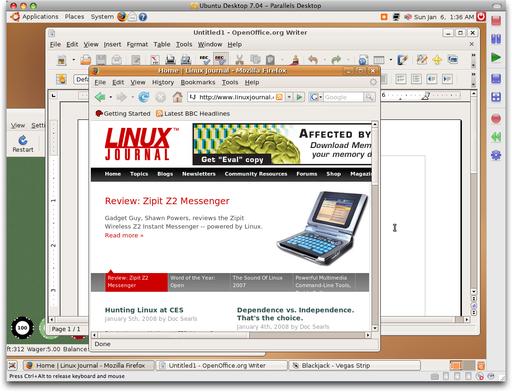

Now it's time to double-click on the virtual appliance images and see what happens. In the case of Parallels, I clicked on ubuntu.pvs, and about a minute later, I was presented with the login window shown in Figure 4. I logged in, and it all looked great, but there was no network connection, which was solved by changing the network option in Parallels Desktop itself from bridged to shared networking (NAT), then clicking network connection on the Ubuntu menu bar. A few seconds later, and you can see the results in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Parallels Desktop running Ubuntu within the Mac OS X world, logged in, on the network and quite usable.

With the VMware Fusion archive, it wasn't as obvious what needed to be double-clicked to get started, but Ubuntu-7.10.vmx seemed like a good choice. It worked, as shown in Figure 6, but notice that the window was far bigger than the Fusion parent window. Additionally, VMware Fusion complained that the VMtools hadn't been installed, which was a surprise given that it's a download I found at the VMware site. Also, the account and password pair didn't work, because it was a different VA image from what I originally had planned. I guessed and lucked out: ubuntu and ubuntu worked, and after fussing with screen resolution settings—but not having to tweak the network settings—I had Ubuntu working within VMware Fusion too, as shown in Figure 7.

In the end, I did have a fully functional Ubuntu Linux running within each of the two virtualization environments—one was sufficiently fast that when I put it into full-screen mode on my 2.3GHz MacBook Pro running Mac OS X Leopard 10.5.1, I really could use it for editing documents, surfing the Net and experimenting with Ubuntu and Linux graphical apps. In fact, I was rather surprised by how snappy the operating system was within these environments, as I'd run Microsoft Windows XP and Windows Vista within the virtualization world and had found it functional, but not comparable to a real PC. Linux within the virtualization world, however, was quite pleasantly snappy and very usable.

This leaves us the fundamental question with which we started, why? If you have a logical reason to run a full Linux distro on your Mac for testing or experimentation, or to gain access to applications not otherwise available within the Mac OS X world, this is a satisfying path to travel.